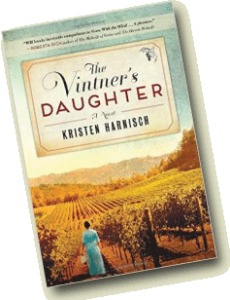

Debut novelist Kristen Harnisch’s The Vintner's Daughter came out not long ago in Canada and more recently in the US. Booklist called it, "a story of perseverance and transcending one’s past," Kirkus Reviews suggested that, "Wine aficionados and fans of romance and historical fiction will drink this in,” and bestselling author Adriana Trigiani had this to say: "Lush and evocative, this novel brings the Loire Valley and its glorious vineyards to life in a story that will delight readers everywhere. Enjoy with your favorite glass of Merlot.” Sounds like a perfect summer read to me!

And for further confirmation, check out David Abrams' My First Time column with Kristen on his brilliant book blog, The Quivering Pen.

As always, I was curious about the story behind the story, especially because The Vintner's Daughter straddles two countries and two types of publishing ventures:

VP: In your author bio, your publisher mentions that your family left France in the 1600s and emigrated to Canada. Your novel,The Vintner’s Daughter, explores the Old World and the New World through the lens of vintners. I wonder how your family’s background influenced your novel’s subject? Did you have firsthand family documents that sparked your imagination?

KH: Absolutely. With regard to my French-Canadian heritage, I have a family tree—researched and written by a Benedictine monk cousin in the 1960s—which traces my grandmother’s ancestry back to Louis Hébert, one of the settlers of Quebec. Although I don’t believe any of my ancestors were winemakers, their journeys from their homes in Normandy and Paris, and eventually their emigration from the St. Lawrence River Valley to western Massachusetts in the1800s, sparked the question: What is it like to leave the only home you’ve known and arrive homeless in a foreign country? In The Vintner’s Daughter, I wanted to answer this question through Sara Thibault’s eyes.

My Irish grandfather also set sail for New York from Ireland in 1921 at the age of nineteen. The ship’s manifest from Ellis Island bearing his name, address, and a note indicating that he was detained in the hospital with the mumps, were the inspiration for Sara and Lydia’s arrival scene in New York. I wanted to recreate, in part, what my grandfather experienced upon his arrival at Ellis Island. His name is etched into the wall there, and every few years I hop the ferry over to the island, to find his name again and remind myself of the sacrifices he made so future generations could thrive.

VP: Tell us a little about the arc of your novel—does your female heroine’s story parallel your own?

KH: Sara Thibault, the female protagonist my novel, possesses a strong, innate understanding of who she is and what she wants at age eighteen. I didn’t at that age, but I do now at age forty-three! Yet, there are similarities in our stories. Early on, Sara defines herself as part of her family’s legacy: her father is a master winemaker, and she will follow in his footsteps. Yet, when her mother sells their vineyard to a rival family, and a violent tragedy compels Sara to flee to America, she is forced to redefine her identity. In my twenties, I also experienced this shift—from defining myself as part of a family unit, to perceiving myself as an individual, capable of making my own way in the world. I think most women experience this coming-of-age moment in some form or another. Sara also experiences great loss, and unfortunately, after my younger brother passed away three years ago, I have come to intimately understand this pain. Losing someone so important changes how you move through the world. This notion is also reflected in Sara’s story.

VP: Often the path to publishing a first novel is long and circuitous. I’d love hear how you came to write and eventually publish yours?

KH: My path to publishing was definitely long and circuitous! I began researching the story for The Vintner’s Daughter in 2000, after a trip to the Loire Valley sparked the idea for a novel. Over the course of the next thirteen years, I took several online writing courses, researched French and California wine history, read nineteenth-century wine trade papers, consulted a master winemaker and reviewed old documents at the Napa County Historical Society. There were many starts and stops along the way!

Soon after I’d signed with my agent, April Eberhardt, in January 2013, Harper Collins Canada offered me a two-book deal. By December 2013, when they announced that they were going to publish The Vintner’s Daughter in Canada in June 2014—ahead of schedule—I was elated. Yet, we had no U.S. publisher, and we were running out of time. I asked my agent about She Writes Press, a partnership press in Berkeley. I belonged to their 23,000-member online writing community, and had heard about their recent successes. Luckily, April knew the publisher well. She pitched my book to Brooke Warner, requested a summer publication date, and we signed!

VP:The Vintner’s Daughteris having success with a conventional large publisher and also through self-publishing. Can you share your perspective on self-publishing? I’m curious if your opinion about that route to publication has changed over the years.

KH: This is an exciting time to be independently published! I’m so grateful that I’ve had the opportunity to work with the expert editorial and creative teams at Harper Collins Canada, but I’ve learned so much through my partnership with my US publisher, She Writes Press. This new partnership-publishing model appealed to me because She Writes Press only publishes projects of high literary quality, and they offer traditional distribution through Ingram Publisher Services. This means that Ingram sales representatives actively market my book to Barnes and Noble, Books-A-Million, etc. and libraries across the country, just as they would a traditionally published novel.

Regardless of which indie path you choose—partnership, DIY (self), or assisted publishing—I believe you can achieve great success if you strive to offer the highest quality novel to your readership. According to Hugh Howey’s latest Author Earnings report, indie-published authors are now earning 39% of e-book Kindle royalties, as compared to Big 5 authors’ 37%.This is exciting news!

VP: You are Canadian by background, but grew up in New England. Your novel first came out in Canada and now in the US. How has straddling the different countries been for you as an author?

KH: My ancestors are French-Canadian, but I was actually born in Maine. Having a book published in Canada and the US (and in Hungary and the Netherlands very soon) has been an interesting cultural study. The Canadians are so welcoming, unfailingly polite, and refreshingly flexible. Just like the United States, Canada has a vibrant reading community. I truly enjoy the interaction with readers through the Harper Collins Canada website, the She Writes online community and through social media.

VP: I also see from your blog that you have a strong interest in parenting issues, and especially the idea of “inspiring moms.” Can you explain what that means to you?

KH: I love being a mother to three children, ages 13, 10 and 5. However, I know how often we moms set aside our creative aspirations to care for our families. Whenever I have time, I like to write blog posts about moms who are pursuing their creative interests while raising a family. For example, my friend Anne Wells, founder of Unite the World with Africa, travels to Tanzania every year to advance women’s health, education and microfinance programs there. Another friend, Scarlett Lewis, who tragically lost her son Jesse Lewis in the Newtown, Connecticut, school shooting, has created The Jesse Lewis Choose Love Foundation and is working to introduce a curriculum of compassion in our US schools to encourage children to choose love over hate. These moms, and many more, inspire me to forge ahead, along my own creative path.

VP: And lastly, do you have any advice for aspiring writers who have a first novel in them?

KH: Yes, I’d like to share two thoughts. First, make sure your novel is well edited. Your manuscript should be free of grammatical errors, should hook the reader by the second page, and should continue to be a “page-turner” from that point on. This seems obvious, but in fact, it takes time and many rounds of edits. Based on feedback from an editor friend and twelve beta-readers, I revised my manuscript seven times before I began to query literary agents. After 23 agents rejected my queries, I revamped the manuscript again, and the 24th agent, April Eberhardt, offered me representation. Patience and persistence are key!

Secondly, imagine your book’s success. Visualize holding your finished book in your hands. What colors do you see? How does it feel like beneath your fingers? Can you smell the fresh ink when you flip the pages? Allow yourself to feel the excitement of that moment! Don’t listen to anyone who does not support the vision you have for yourself and your book!

(Kristen's author photo is by Alix Martinez Photography)

DSL: The book was a total mess to begin with, as most first drafts are. Catherine was much older and the style of the writing was fairly stilted, Henry Jamesian. I wanted to write a 19th-century novel and set it in the present. I showed my writing group at the time a couple of chapters and they all said the same thing—it need a facelift. So I gave it a facelift. I made Catherine much younger and I updated the language to make it more germane to the current culture, because of course it's your job as a writer to please everyone but yourself. Haha. But something began to happen when I began to shake the dust off it. It entered a different phase of life, younger, more vibrant, and I thought, I can still write a 19th-century novel because I'm dealing with 19th-century themes and people. All of my characters long to live in a different era, an era before television and the Internet (the book is set in 1991, long before cell phones and the Internet), an era that was far more simple and more connected. I find that our era is so fractured and discombobulated that it's no wonder certain books flourish. They reflect the culture in which we live. Well, I wanted to write a novel that reflected a culture in which we don't live. Even though it might have a similar look and feel to our current millennium, it isn't. It's otherworldly, even old worldly, and the characters in the novel behave as such.

DSL: The book was a total mess to begin with, as most first drafts are. Catherine was much older and the style of the writing was fairly stilted, Henry Jamesian. I wanted to write a 19th-century novel and set it in the present. I showed my writing group at the time a couple of chapters and they all said the same thing—it need a facelift. So I gave it a facelift. I made Catherine much younger and I updated the language to make it more germane to the current culture, because of course it's your job as a writer to please everyone but yourself. Haha. But something began to happen when I began to shake the dust off it. It entered a different phase of life, younger, more vibrant, and I thought, I can still write a 19th-century novel because I'm dealing with 19th-century themes and people. All of my characters long to live in a different era, an era before television and the Internet (the book is set in 1991, long before cell phones and the Internet), an era that was far more simple and more connected. I find that our era is so fractured and discombobulated that it's no wonder certain books flourish. They reflect the culture in which we live. Well, I wanted to write a novel that reflected a culture in which we don't live. Even though it might have a similar look and feel to our current millennium, it isn't. It's otherworldly, even old worldly, and the characters in the novel behave as such.